Good day! It’s been a while since you received my irregular newsletter. But here it is again. I have been busy with a lot of research over the past few months, mainly with a focus on the gig economy. I am also working with the WageIndicator Foundation towards an inspiring conference we are organising in Pune, India. And we are future-proofing GigCV, the data sharing agreement scheme for gig platforms that currently impacts 100,000 workers and has already been used 28,000 times by workers. Plus many other activities in the platform economy that I won’t bother you with right now 😉 In this edition, I share my take on the failure of the European Platformwork Directive, I show how platforms (should) share data with the tax authorities and I have listed some other insights for you. If you have any questions following this edition: press the reply button. Have a great day! Martijn Arets

R.I.P. Platformwork Directive (and now on the move again)

Last week was the last attempt to get something more of the watered-down European ‘platformwork directive’ off the ground. Unfortunately, once again member states failed to reach an agreement and the future of the Directive looks pretty bad.

I have written several times about this directive. Bottom line, my reflections boiled down to the following:

- Combining presumption of employment relationship and impact of technology on the worker, the directive was a tricky one right from the start. My advice was and is to pull the two apart;

- The directive distinguishes between those who find (mostly precarious) work through a platform and those who find the same work through other channels, so I really saw a possible success of the directive as a starting point, but a somewhat cumbersome one (but if it works, it works. But it doesn’t work, unfortunately…);

- There is a danger that, as with the AB5 legislation in California at the time, platform companies will modify their systems and algorithms so that they do not fall under the criteria. A small ‘effort’ resulting in a potentially long cat-and-mouse game.

And so now there is no platform directive at all. Which has shown that agreeing something on labour market at European level is extremely difficult. And governments throw the biggest bullshit arguments (spurred on here and there by the lobby of platform companies) on the table to get out of it. France, for example, thought the directive was a danger to innovation. I am curious in which definition of innovation ‘undermining workers’ rights’ is included. I would be happy to receive a link.

What next? I cannot imagine that this is an end point, and I also do feel that too many national stakeholders waited too long to take their own measures, hoping that the directive would come anyway. I hope these stakeholders will now quickly work their own plan and possibly work together. What policymakers could do now:

- Enforce. Indeed, in many cases regarding the classification issue, no new legislation was needed at all, but can be solved under current labour law (regardless of whether the working with a subcontractor model is better off). Meanwhile, more cases are won than not in Europe;

- From silo (vertical) to horizontal law. Actually, it was already odd that, on the one hand, certain laws would apply to a worker based on how a transaction had come together. I can also imagine that parts of the directive on which we did agree are now the subject of separate agreements. For instance, making automatic decision-making processes explainable, prohibiting (and this already falls under AVG, so: enforce) ‘robo-firing’ (being fired by the algorithm) and directing and encouraging data portability (which also already falls under AVG, so again: enforce).

- More focus on new platform-specific pain points. Taxi drivers were freelancers before Uber, so it is questionable why that is the problem now. What is the problem is that there is unclear and non-transparent (personal) pricing, workers do not make informed decisions, there are no fixed prices (no one knows what the fare will be in 2 months’ time), the apps try via gamification to ‘nudge’ the driver to do what is in the app’s best interest and more. Or in the case of delivery: the worker being paid per job (which does not contribute to traffic safety) and sitting on the phone during the ride. And actually in general: how the risk of no work (and everything that comes with it) is shoved entirely on the shoulders of the working person.

Because maybe getting everyone into (subcontractor / temp) employment would be a nice goal, but we should also not (like too many stakeholders) be too naive that an employment contract is going to solve all the problems. There are other ways to get what you want to achieve done. In New York, for example, a minimum rate has been agreed for delivery workers with positive results (read this piece):

The city’s new minimum pay rate for delivery workers, which went into effect late in 2023 after numerous legal challenges, is incentivising workers to slow down, stop at red lights, and follow the rules of the road – transgressions that have become commonplace within the industry as workers perilously rush to deliver someone’s chicken fingers before they get cold.

I wonder what the next steps will be. As mentioned more than once, I was not a fan of the directive, as it was too generic and completely ignored the non-platform market, but nevertheless, it would have been a nice starting point of improving the labour market. And that you, as a consumer, then have to pay a bit more for your pizza delivery (like in New York where platforms raised delivery prices by $2), so be it. That’s the price of labour. The customer ordering a pizza will also want to be paid decently for their own labour.

What I mainly hope is that the Platform Work Directive process has put the issue of precarious workers on the map. Before the platform discussion, there was no European and national focus on the position of delivery drivers and taxi drivers, and almost no policymakers, union leaders or academics had this target group on the agenda.

The directive process has revealed what the pain points are, and is now giving national governments the kick in the pants to work on this at the national level. If that is the case, those 800 days of wrangling over that directive will not have been in vain.

How tax authorities are watching sellers on platforms like Amazon and Vinted thanks to DAC7

Platforms centralise fragmented and mostly non-visible markets. This gives them an overview of a market and its transactions that previously no one had. In addition, digital systems allow them to coordinate certain issues centrally. In France, a domestic cleaning platform whose founder I recently spoke to settles the subsidy on hiring home cleaners directly through the platform. This saves the government a huge amount of money in export and makes it low-threshold for consumers to buy subsidised services. No hassle of advancing and settling, just ‘real time’ execution of subsidy.

Taxation via platforms has also been discussed for quite a few years. It is of course an attractive strategy for a tax authority: taxing activities that were previously virtually invisible and so small and fragmented that supervision and execution were enormously expensive. The first conversations about this started at one of the workshops I organised when I was still working part-time at Utrecht University. I thought it was time for everyone who talked about each other to start talking to each other. To discover that there are normal people behind the anonymous institutions that are part of the debate.

In that period (2017-2019), the Dutch Tax Authorities organised a first session on the question: can we also tax via platforms? Not much later, the City of Amsterdam finalised the deal with Airbnb whereby Airbnb would levy tourist tax via the platform for the municipality. In its turn, the municipality would monitor this somehow.

At the European level, there has been work in recent years on legislation requiring platforms to pass on data from a certain category of providers on a platform. Think of gig platforms, second-hand marketplaces, websites for (short stay) accommodation and more. During the event ‘Towards a workable regulation for the European Platform Economy’ that I organised from The Hague University in collaboration with Considerati and PwC (check the report), this legislation also came up.

Last week was the first time platforms had to submit data to the tax authorities. This was therefore the reason why the topic was highlighted in various media.

A few things strike me and some questions remain:

- There is still a lot of ambiguity: even in the items in the media, it could not be said unambiguously when your data is passed on and when it is not. In other words, what are the criteria?

- After inquiring with platforms, I get that there is also a lack of clarity about when as a platform you are or are not covered by DAC7. A number of platforms I spoke to have only organised it ‘just to be sure’, as they could not get an unambiguous answer as to whether or not they would fall under DAC7.

- Platforms are now required to collect a lot of personal data from the accounts they have to transmit data from. It remains to be seen whether this is proportionate.

- Platforms will be required to transmit this data, but I am particularly curious to know whether the Tax Office has the capacity to do anything with this. In an article in the media, I read that the Dutch Tax Administration needs almost 200 extra people to implement DAC7. This at a time when the Tax Administration is facing huge staff shortages.

What the Dutch Tax Administration is doing here is actually partly outsourcing exports to the market. Of course, this is essentially nothing new: for example, employers also collect social contributions and taxes for their workers on behalf of the tax authorities. This creates quite a regulatory burden, especially for smaller platforms. Will we soon see new DAC7 service providers taking care of smaller platforms in this area? After all, many SMEs also use a payroll administration firm. Just an idea… It is important to evaluate after 1-2 years whether this regulatory burden is proportionate.

I think DAC7 is a very interesting case to keep an eye on to see how leveraging the central role of a platform in a fragmented market can lead to benefits in export and allocation of subsidy, for example. I plan to dive further into this soon. So, to be continued.

Floor van Haaren (Cocoroco) on remote customer service, fair pay, and the future of the global labour market

The first episode of The Gig Work Podcast, a podcast about global developments in the gig economy which I produce on behalf of the WageIndicator Foundation, from 2024 was released last week. In the 9th edition of the podcast, I talk to Floor van Haaren, founder of remote customer service platform Cocoroco.

Besides the podcast, a blog about this conversation was also published. You can read it on the Gigpedia website: a joint initiative of the WageIndicator Foundation, Fairwork and the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest.

The Gig Work Podcast is available at Apple Podcasts, Springcast, Google, Spotify, Stitcher, Pandora, and Pocket Casts.

The impact of AI on platforms

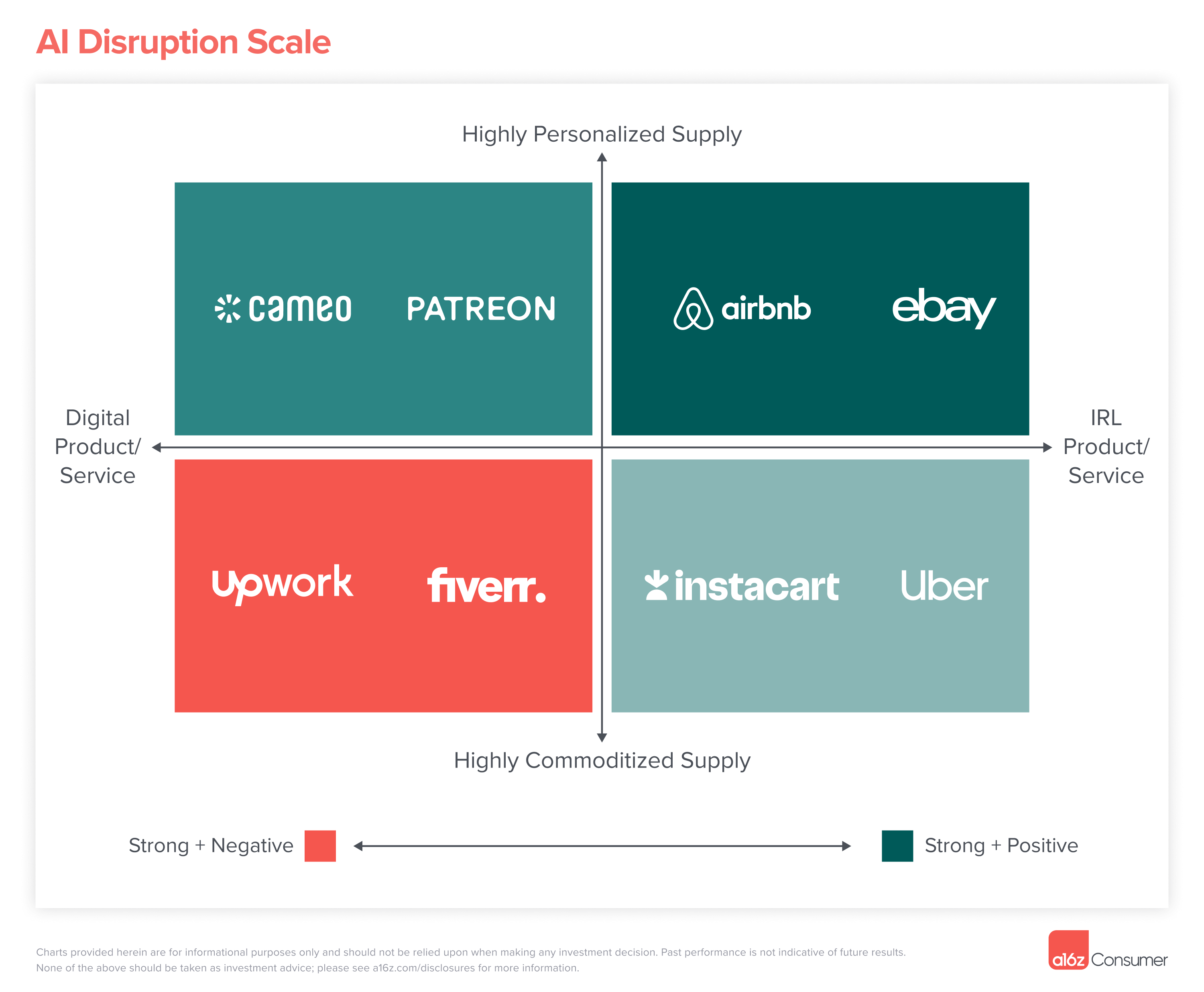

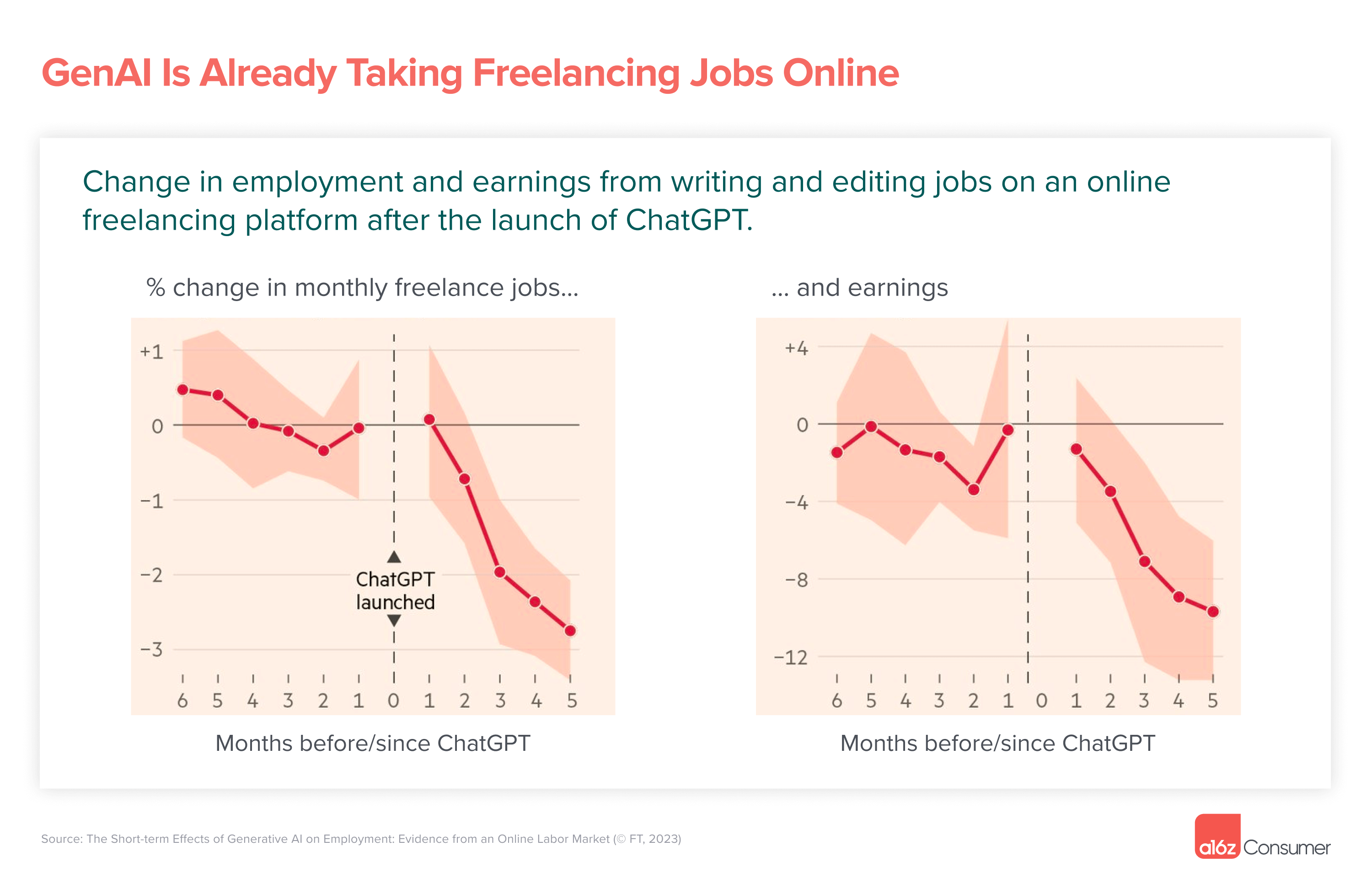

Recently, the piece ‘Marketplaces in the Age of AI came along on the website of Andreessen Horowitz: a major tech investment club. If there is one piece on AI and marketplaces that you should read this week, it is this one. The piece looks at the (potential) impact of AI on the supply and demand side. These two images struck me the most:

The article does not go further into depth on how platform organisations are already deploying AI for their own operations. That will certainly vary from platform to platform. I recently spoke to a platform entrepreneur who deploys AI to detect certain combinations of words in chats between customers trying to circumvent the platform. In that respect, of course, AI has been woven into the platform economy for a (very) long time. But this particular piece gives a nice insight into the big changes that might be coming.

About and contact

What impact does the platform economy have on people, organisations and society? My fascination with this phenomenon started in 2012. Since then, I have been seeking answers by engaging in conversation with all stakeholders involved, conducting research and participating in the public debate. I always do so out of wonder, curiosity and my independent role as a professional outsider.

I share my insights through my Dutch and English newsletters, presentations and contributions in (international) media and academic literature. I also wrote several books on the topic and am founder of GigCV, a new standard to give platform workers access to their own data. Besides all my own projects and explorations, I am also a member of the ‘gig team’ of the WageIndicator Foundation and am part of the knowledge group of the Platform Economy research group at The Hague University of Applied Science.

Need inspiration and advice or research on issues surrounding the platform economy? Or looking for a speaker on the platform economy for an online or offline event? Feel free to contact me via a reply to this newsletter, via email (martijn@collaborative-economy.com) or phone (0031650244596).

Also visit my YouTube channel with over 300 interviews about the platform economy and my personal website where I regularly share blogs about the platform economy. Interested in my photos? Then check out my photo page.