Albert Cañigueral Bagó is fascinated by technology, platforms and the world of work. How did the sharing and gig economy develop? And what impact does technology have on workers now and in the future? This is what Martijn Arets discusses with him in The Gig Work Podcast of the WageIndicator Foundation.

The platform economy has undergone a considerable (r)evolution in 12 years. I myself have been exploring platforms and their impact on people and society since 2011. I was not alone: during my quest, I met several other explorers. One of my travelling companions is Albert Cañigueral Bagó. In 2011, he started the first Spanish blog on the sharing economy. Not much later, he came into contact with the organisation Ouishare, an international partnership of freelancers. “For me, the sharing economy was personally interesting because I don’t value property much,” he says. “I have a rented house, very little stuff. In addition, I saw many benefits for society and the environment. At Ouishare, I found like-minded people.”

Ouishare: a mix of visions

I first encountered Cañigueral in 2013, during the famous ‘Ouishare Fest’. This was a festival at Parc de la Fayette in Paris where 1,500 entrepreneurs, professionals and activists gathered to discuss the development of the sharing economy. “The special thing was that we brought together all the different perspectives,” Cañigueral says. “We at Ouishare were activists, we loved open source. For us, the success of big companies like Uber and AirBnb was disappointing. Still, we managed to have good conversations with these tech entrepreneurs about the future of sharing.”

This was also necessary, he says. “In Spain, delivery platforms Deliveroo and Glovo had just started and that led to conflicts immediately,” he says. “Logical. After all, the inventor of the boat is also the inventor of the sunken ship. The negative effects of platforms can never be completely avoided, but if we work together we can ensure that the positive effects prevail.”

Utopias for the world of work

When it comes to platform work, the biggest problem is the skewed power relationship between the platform and the platform workers, he says. A few years ago, he wrote a book on macroeconomic trends and their impact on labour: El trabajo ya no es lo que era (‘Work is not what it used to be’). In it, he explains, among other things, how the industrial revolution is transitioning into the digital revolution. “During the previous revolution we were children, now we are parents,” he says. “Now we also have to behave like adults. That means facing the facts and taking responsibility: we cannot ignore developments, we have to respond to them in a smart way.”

We work differently in the digital age and platform work fits in with that, he explains. “The idea that a job always has to be 40 hours a week is outdated. Part-time, flexible or freelance work sometimes fits better with all the other pursuits in modern life, for example volunteering or taking care of our family.”

We are still in the middle of the transition, he says. His book contains seven utopian situations for the future of work and technology. “We can use these visions to approach a future where the positive effects of technology outweigh the negative.”

Collective action and cooperation

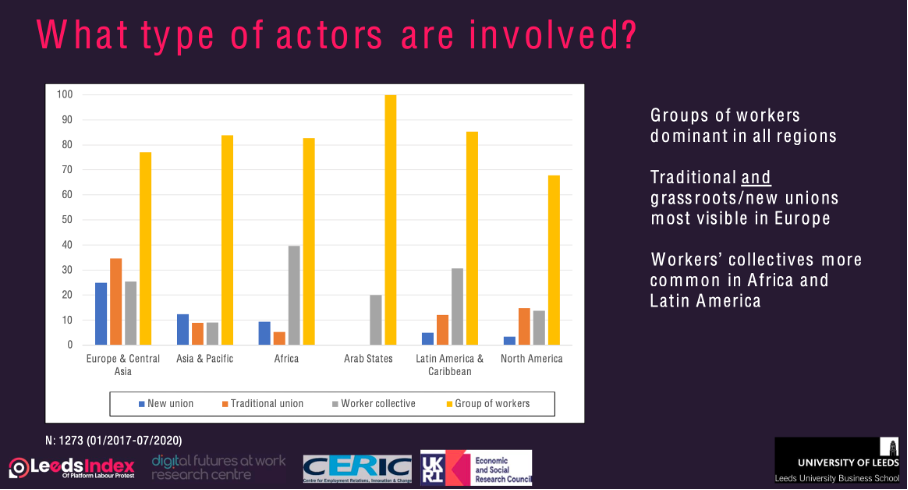

Previously, unions, for instance, protected workers from employers. Such collectives made for a less skewed balance of power. In a fragmented world, collaborations are more important than ever, Cañigueral stresses. “Platforms provide structured access to fragmented and often invisible work,” he explains. “But if the conditions in doing so are not clear or if you cannot influence them, you feel like a slave to the platform.”

Therefore, he says, new collectives are needed. As an example, he mentions the Worker Info Exchange, a non-profit organisation that helps platform workers gain insight into the data collected about them during their work. Read more in this interview with founder James Farrar.

That does not necessarily mean the end of existing unions, says Cañigueral. “Some will disappear, others will reinvent themselves. Collaborating with new initiatives is incredibly valuable. If they are willing to learn from each other and set up collective actions, it ultimately delivers more for working people.”

WorkerTech: collective facilities for those not in an employment relation

Platform workers lack collective services in addition to representation. As freelancers, they have to find their own ways to cope with retirement, disability and illness. So-called ‘WorkerTech’ are solutions to this. They are collective services especially for Glovo delivery drivers, Uber drivers or Fiverr freelancers, for example. Interestingly, WorkerTech is usually not reserved for one type of platform worker. Often such initiatives are open to freelancers working through various platforms.

For example, Pulpo.Life, a Latin American startup that arranges health insurance for platform workers and freelancers. Another example is Nippy, an Argentinian startup that offers all kinds of services for freelancers: from bank accounts to insurance. Cañigueral: “These kinds of initiatives prove that a permanent contract is not the only way to provide decent working conditions and collective services to workers.

Cañigueral does not see WorkerTech as competing with public social security, but complementing it. “The government can learn from such initiatives. For example, such startups know better how to use data to respond to individual needs. But that requires mature politics.”

Analysis

Catching up and looking back with this good friend on the development of the platform economy gave me new insights. We both started our research journey in the sharing economy and later turned the focus to the job and platform economy and the future of work. The impact of technology on people, organisation and society was the common thread.

Cañigueral explains that we are in the midst of a major change. In my opinion, platforms are a logical testing ground for technologies that will eventually impact the entire labour market. Just look at WorkerTech, which was born out of a platform economy need but also offers many benefits for other workers. Increasingly, WorkerTech is also available to all workers: self-employed, employees or them working in the informal market. The reason these kinds of startups fit the needs of modern working people so well is because they can develop and adapt faster than existing institutions.

Finally, we discussed how social security can be shaped. It will be interesting to explore how we can ‘re-bundle’ these kinds of securities so that they do not only suit permanent salaried employees, but are of use to all kinds of workers.

Indeed, in the Western world, many securities are linked to the permanent contract, but this is not the case at all in many parts of the world. Moreover, in many countries the informal labour market is large: in Latin America, some 56 per cent of people work in the informal market. At other places in the world this percentage is even (much) higher. Currently, they are invisible to all institutions and have no protection at all. Platform work, as a gathering place, can give structure to this fragmented group of informal workers, bring them together and give them access to the securities and protection of WorkTech. So, especially in the non-Western world, this can be a substantial improvement.

This blog and podcast were also published on Gigpedia.org