In the discussion about platform work, I keep bumping into a big dilemma. Online platforms offer a fast -access solution for work and income in the short term. At the same time, they often fall short in providing good working conditions, sustainable careers, and future perspectives. In my opinion, this tension is the most important challenge for the future of work. How do we solve it?

Frida Mwangi knows all about it. She made the transition from housewife to platform worker, and then went on to become an entrepreneur and union leader. As a founding member of the Kenya Union of Gig Workers (KUGWO), she champions the rights of Kenyan platform workers. Her lessons are relevant not only for Kenya, but for the platform economy worldwide. I spoke to her for a new episode of The Gig Work Podcast by the WageIndicator Foundation during my visit to Nairobi, Kenya.

A new start

Mwangi knows from her own experience what opportunities and perils the platform economy can offer. After being a full-time motherand housewife for 17 years, she wanted to return to work. Not only to earn money, but also to set an example for her children. But without recent work experience or references, a regular job was out of reach.

Then she discovered Upwork, one of the largest international platforms for freelance work. After a short training course, she was able to start working right away. Her first job was converting audio into text (transcription). “I could work from home in my own time, which was ideal in combination with raising my children and running the household,” she says. “In the beginning, it was exhausting because it was my very first job. At the same time, it felt like confirmation: ‘Oh, this is real. And it’s something I can actually do.’ It felt like a chance for a new life.”

Learning from others

Mwangi once wanted to become a lawyer, but that didn’t happen. She was still eager to learn. She discovered all kinds of online communities where platform workers shared knowledge and experience. “I learned a lot from that, both about the work and about how to earn more,” she says. “Those communities were incredibly valuable. In no time, I had more work than I could handle. I was able to outsource my surplus work through my own small business: Kazi Remote.”

This shows that platform work can be a stepping stone to employment and self-employment. But Mwangi also quickly discovered the negative aspects.

Unilateral conditions

Firstly, working conditions and earnings could change suddenly. Initially, she earned between $15 and $20 per assignment, later rising to $100 when she specialised in legal, financial and academic transcription transcription assignments. “As more people started working via Upwork, it became more difficult to get jobs,” she says. “The problem was that you had to bid on assignments, and that system was unreliable. Some days you kept bidding without getting any work.” The work also shifted from transcribing to proofreading AI-generated transcriptions.

Then Upwork introduced a new system. Platform workers had to buy credits to bid on a job. “To maintain a secure position on the platform, you sometimes have to spend up to $45 a month on credits,” says Mwangi. “For those coming from a financially vulnerable situation, that’s a significant barrier. The platform suddenly made the workers bear all the risks.”

Exclusion and slow payments

What’s more, the algorithm could exclude you for no reason. “Sometimes you would wake up and find that your account had been blocked without warning,” she says. “Often you would be reinstated automatically, but that took a while. In the meantime, you lost income.”

Platforms did not take responsibility, she says. ‘In the beginning, PayPal was not accessible to the African region. When the service did become available, accounts were regularly closed, even though the workers’ money was still in them. And payments were sometimes delayed by months. When we had complaints, no one was available to help us.’

Internet waste and mental damage

Ironically, Frida’s activism began through an initiative of the platform itself. During an Upwork event, she met other freelancers and discovered that she wasn’t the only one with problems. She also heard dire stories from colleagues in content moderation and data labeling. This is the work where people have to remove illegal or offensive texts or videos from platforms and train algorithms to recognize this type of content.

“Many thought they were going to do translation work, but instead had to filter harmful content on a daily basis,” she says. “It was garbage, internet garbage that you had to sift through. And the more you take in, the more harmful it is to your mental health.”

‘Platforms don’t offer a career’

She also saw that while platforms offered a stepping stone to work, they didn’t really help workers progress. “If I had stayed stuck in my transcription work, I would hardly have any assignments now,” she says. “This type of work has now been largely automated. That applies to more jobs via platforms.”

Tech companies offer a low barrier to entering the workforce, but rarely offer opportunities for advancement, training, or guidance. Mwangi: “I realized that platforms don’t offer you a career, but are only suitable as a temporary place to earn money. Yet many people become dependent on them, precisely because of the lack of opportunities for advancement.”

Organized action is not easy

She also heard more and more stories about underpayment in location-based work, such as taxi services. All these stories touched her deeply and brought back an old dream: to become a lawyer. She felt a strong urge to stand up for platform workers. Mwangi: “I believe that platforms must take responsibility, both in terms of working conditions and pay, as well as in terms of long-term prospects.”

Her first attempt to set up an association in 2019 failed. “No one had any experience with organizing,” she says. “Moreover, organizing is not easy in the platform economy. Whereas in a factory hall it is easy to talk to colleagues about problems, platform workers sit alone at home. There is also a gap between the different types of work. Online freelancers feel different from Uber drivers, for example.”

But she did not give up, because she was convinced that collective action was necessary. In 2024, she succeeded: together with other platform workers, they founded the Kenya Union of Gig Workers (KUGWO). It is the first Kenyan trade union dedicated to improving working conditions, wages, and rights for all types of platform workers.

‘It’s a matter of taking responsibility

Mwangi’s vision: platforms can offer both short- and long-term benefits for workers. “It’s a choice for companies whether or not to participate in exploitation,” she says. “That doesn’t just apply to the platforms themselves. Their customers are often large Western corporations. These companies must not forget the ‘S’ (Social) in the ESG principles (Environmental, Social, and Governance).”

KUGWO is keen to work with tech companies to put the interests of workers first. A good example is the collaboration with Microsoft/LinkedIn Learning. The Kenyan union pointed out that platform workers who lost their jobs due to automation had no opportunities to improve their skills. After consultation, Microsoft offered eleven free courses (such as project manager or software developer) as a stepping stone to better work. Mwangi: “This proves that even in a complex relationship, you can find concrete and sustainable solutions.”

The power of strong unions

Finally, I spoke to Mwangi about political influence and regulation. According to her, the voice of workers in Kenya is systematically ignored by policymakers. Her appeal to the rest of the world is therefore clear: “Build stronger institutions that enable workers to exert more influence. Support them, for example with legal and technical expertise. Employers and governments already have so much power, while workers are in a weak position.”

Mwangi emphasizes that you need financial independence and a strong membership base to be able to negotiate at all. She knows from experience how difficult that is. Nevertheless, with her resilience and perseverance, she has already achieved a lot.

Finally: is it a dilemma?

Mwangi’s call echoes earlier conversations I had, such as with Ephantus Kanyugi of the Kenyan Data Labelers Association. This is not an official trade union, which is precisely why it is fast and flexible. Mwangi chose a different route: establishing a formal union, with all the bureaucracy and political dynamics that entails. In practice, they are complementary. They have different strategies but a shared goal: better working conditions and pay for platform workers.

I agree with Kanyugi and Mwangi: what is needed in the short term and what is important in the long term must go hand in hand. Quick and easy access to work, with security and future prospects. Especially when the clients are companies, they must take responsibility and not shift it onto individual workers. Clients and platforms must choose: do they contribute to exploitation, or do they help build prospects for workers worldwide?

Upcoming events

On Wednesday 29 October from 15:00 to 16:30 CET, I will be speaking at the online seminar ‘Sustainable Platform work – Studying trust and reputation systems in the platform economy’.

In this webinar, we will discuss the reputation systems that assess workers, and I will present my KlusCV case study to show how data portability can work in practice and what questions we need to ask about it.

For more information and to register, please visit this link.

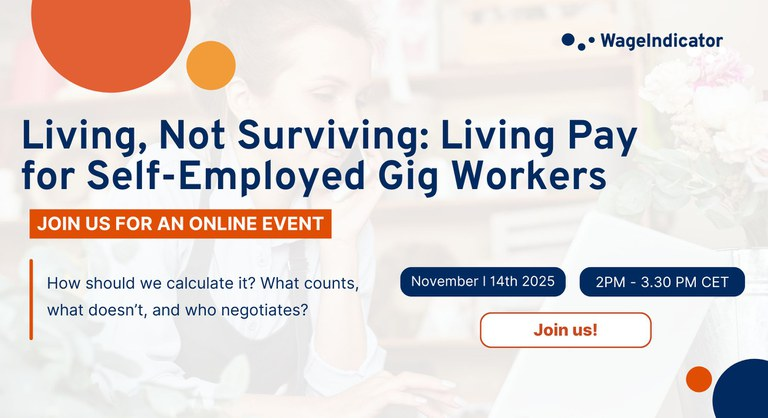

On Friday 14 November, on behalf of WageIndicator, I will be organising the online webinar ‘Living, Not Surviving: Living Pay for Self-Employed Gig and Platform Workers’ from 14:00 to 15:30 CET.

During this webinar, we will explore how we can calculate a minimum rate for self-employed platform workers, why this is important, and learn from two inspiring cases how to apply such a rate in practice. This event connects to the Living Tariff (Living Tariff) that I have been working on for several years, in which we calculate a minimum hourly rate for self-employed workers that covers the cost of living, in line with the Living Wage methodology. This is because minimum wages usually only apply to employees, while 46% of the global workforce are not employees. In light of the ILO Platform Work Convention, we will therefore be discussing with a broad group of stakeholders how we can achieve this. I look forward to it and welcome you to join us!

For more information and to register, please click on this link.

Reflections on previous events this month

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to contribute to a meeting organised by the International Society for Labour and Social Security Law in collaboration with the Levenbach Institute. The theme was “The role of social partners in the use of AI at work”. In this blog, I share my findings.

Last week, I organised the event “Ghostwork, the invisible labour behind AI” at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. The aim was to raise awareness of the fact that behind AI there are tens of millions of vulnerable workers who annotate and check the data, thereby keeping AI running. And to start a conversation about how we can improve these conditions. You can find my findings and a link to the recording here.

Following my blog post ‘From Bologna to Big Tech: critical lessons about data work and AI’, I was approached by Ing. Amir Sabirović, who asked if he could interview me for his AI Almanac podcast. It turned out to be a fun and open conversation about technology, choices, power, data work and dependency. A glimpse into the (chaos) in my head 😉

Aflevering op Spotify

Aflevering op Youtube