The growing impact of digital technology, generative AI and algorithmic management on work is an increasingly widely explored topic. Last week during the two-day conference ‘Future of Work: Reclaiming the value of work in the digital economy’, researchers from across Europe gathered to present their work and exchange views.

It was organised by both the research group of the ERC project ‘Respect Me “ and the European Trade Union Institute” (ETUI). In this blog, I look back at the discussions and my own contribution on an upcoming paper on the Living Tariff methodology.

From focus on platform to focus on impact of technology on work

The shortcoming with many discussions on the platform economy and platform work is that it is assumed to be an isolated phenomenon. A self-contained silo. I wrote earlier that this is of course big nonsense: you cannot talk about platform work while ignoring the rest of the labour market. So that has been my biggest criticism for ages of how unions relate to this development. They often ignore what the (often poor) conditions of workers are in the same market where a platform does not provide intermediation and that the alternative for the worker is not a well-paid job with a lot of security. For me, this was most visible in the case where FNV sued domestic cleaning platform Helpling. When you have a discussion about domestic cleaning platforms without acknowledging that it takes place in a sector where informal work dominates in most countries, you deliberately miss an opportunity to do something for this group of workers.

It is therefore first important to look at what is really new. I did this in 2021 together with Jeroen Meijerink in our research ‘Online labour platforms versus temp agencies: what are the differences?’.

Also at the conference in Leuven, the call to look at what is really new was highlighted by Uma Rani of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), among others. She brought an interesting overview of a historical perspective of the use of technology in the context of work and also showed that sometimes the technology itself does not change, but the way it is applied does. This was also discussed by her ILO colleague Annarosa Pesole.

The platform economy is often seen as the ‘nursery’ or ‘sandbox’ of the labour market, where these technologies like algorithmic management are developed and tested (which raises important ethical issues) on workers. To then be applied to the wider labour market. Something that, by the way, is in line with the current development of legislation like the Platformwork Directive, which everyone understands that the passages on algorithmic management should apply not only to a specific group of platform workers, but to all workers.

And so that was the focus of this conference: the impact of digitalisation on the way we work, organise, allocate, control and (to some extent) evaluate work. Where the predominance was on the worker’s perspective, which is not surprising with the ETUI as co-organiser. There was much discussion on how to secure workers’ voices in the governance of this technology, how to make processes more transparent (and verifiable) and how to increase knowledge among workers and unions.

Insufficient use of existing regulation

There is a lot of focus on new regulation in the platform economy. In addition to the previously mentioned Platformwork Directive, a platform law to be implemented nationally in all European member states over the next 18 months, we also have the Digital Service Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DSA), Platform to Business Directive (P2B) and others. The focus here is on creating more transparency and accountability with the aim of improving the balance of power between the different stakeholders (platform, worker, client and society).

💡

Read a report on a meeting on workable regulation I organised earlier and a review of the DAC7 platform law

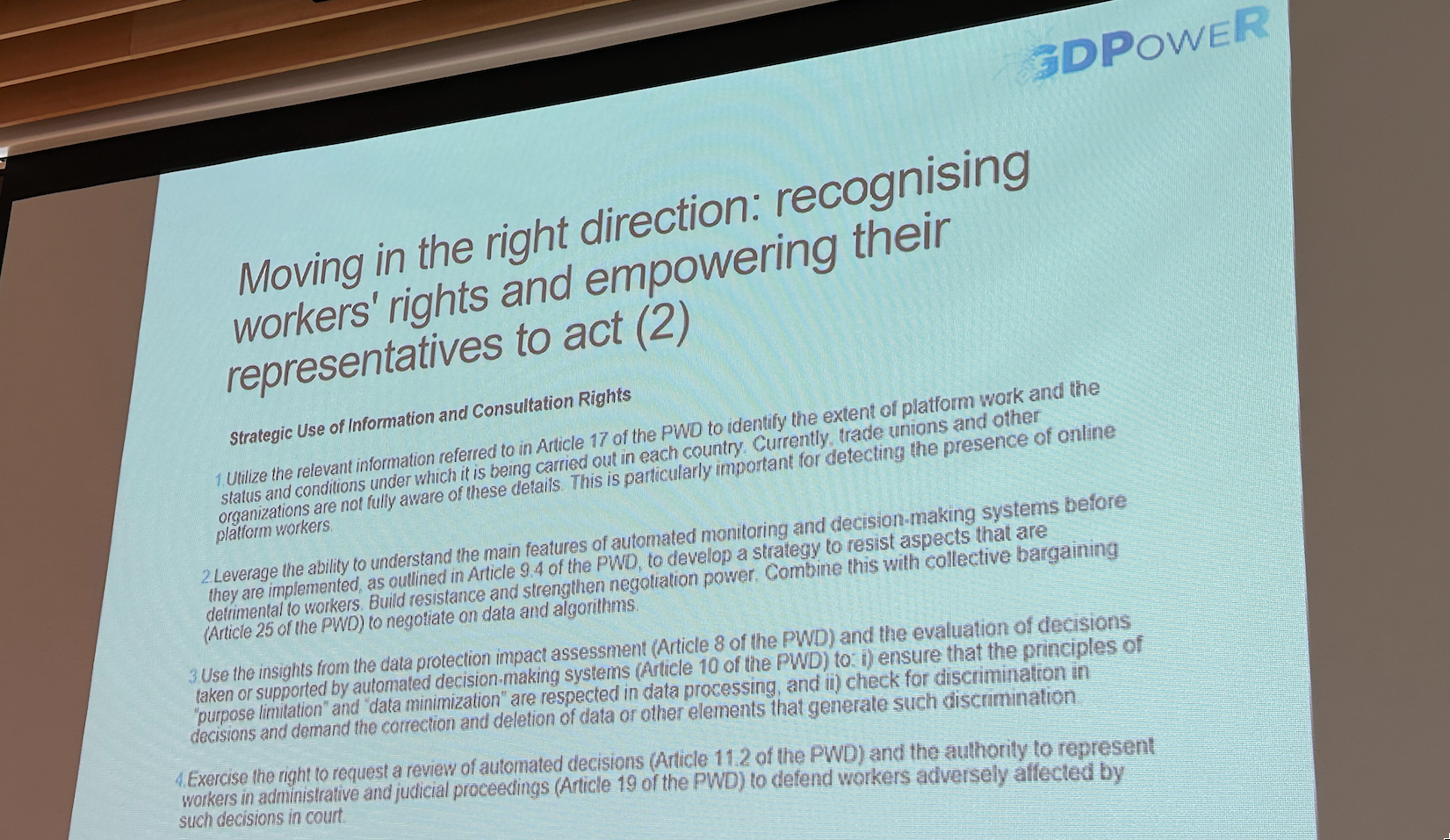

With all the attention around new regulations, you would almost forget that there is already a lot of regulation that working platforms already have to comply with. During the session ‘Representing workers rights in the platform economy’, among others, this was emphasised several times. This session was mainly about the upcoming Platformwork Directive, but also explicitly about GDPR. Since many platform workers are not employees, they are also not protected under employment law, making AVG for rights relating to data suddenly very interesting. (note: I am not a lawyer) For example, María Luz Rodríguez Fernández presented the GDPoweR project, which , according to its own website, ‘explores what worker data is collected by platform companies and how this affects workers, what strategies are used by social partners to negotiate and implement collective agreements and how the implementation of such agreements can be monitored and enforced. A central method used is the recovery of worker data through GDPR requests and the joint analysis of this data by workers and researchers.’ The slides below summarise the initial findings.

And although GDPR is an individual and not a collective right, the GDPoweR project shows that there is no reason not to use it for collective activities. Something I also described earlier in the blog and podcast ‘knowledge is power, even in the platform economy’ following an interview with James Farrar, founder of the Worker Info Exchange. All the cases his modern union brought against Uber, among others, were won on the basis of existing regulations. Something policymakers and unions should consider a lot more.

And of course, new regulations also provide opportunities. Personally, as a non-lawyer, I expect little impact from the employee part of the upcoming Platformwork Directive. It would be strange if your rights as workers depend on how you get your work handed to you. I see this part more as a stepping stone to better rights for an entire sector, although with the current political climate, the words ambition and political unity are rare. I am particularly curious to see how the excerpts dealing with the impact of technology on work are fleshed out. On the one hand, because certain things are contract-neutral (this sounds boring, but is revolutionary, as all certainties and obligations around security, among other things, are linked to being an employee) and, on the other hand, because there is a mention of ‘digital community channels’ that should break or reduce the isolation of individual workers (and thus an important instrument of platform power).

Finally, Annarosa Pesole (ILO), among others, warned on the finding that more and more parties are using ‘off the shelf’ technology and thus have little knowledge, insight or influence on the technology being deployed. A danger for the worker, but also for the one deploying the technology, as from the AI Act, among others, there is also a responsibility on the user of this technology.

Caught in the worker paradox and union dilemma

Many discussions on platforms and labour have revolved around whether the worker is a freelancer or an employee. In itself a logical thought from a Global North perspective, because there, being an employee is the dominant model and many securities and obligations are linked to this contract model. In addition to social securities, I am talking about health and safety obligations, but also a role in social dialogue and representation. If you are not an employee, you are virtually outside the scope of this.

Although I can understand the focus, I do question to what extent the discussion is not caught in an employee paradox, a term that also came up during this congress. This is because in many countries, the worker model is not the dominant model and because this focus ignores a large group of workers who also need protection. Think of freelancers, but also of the informal market.

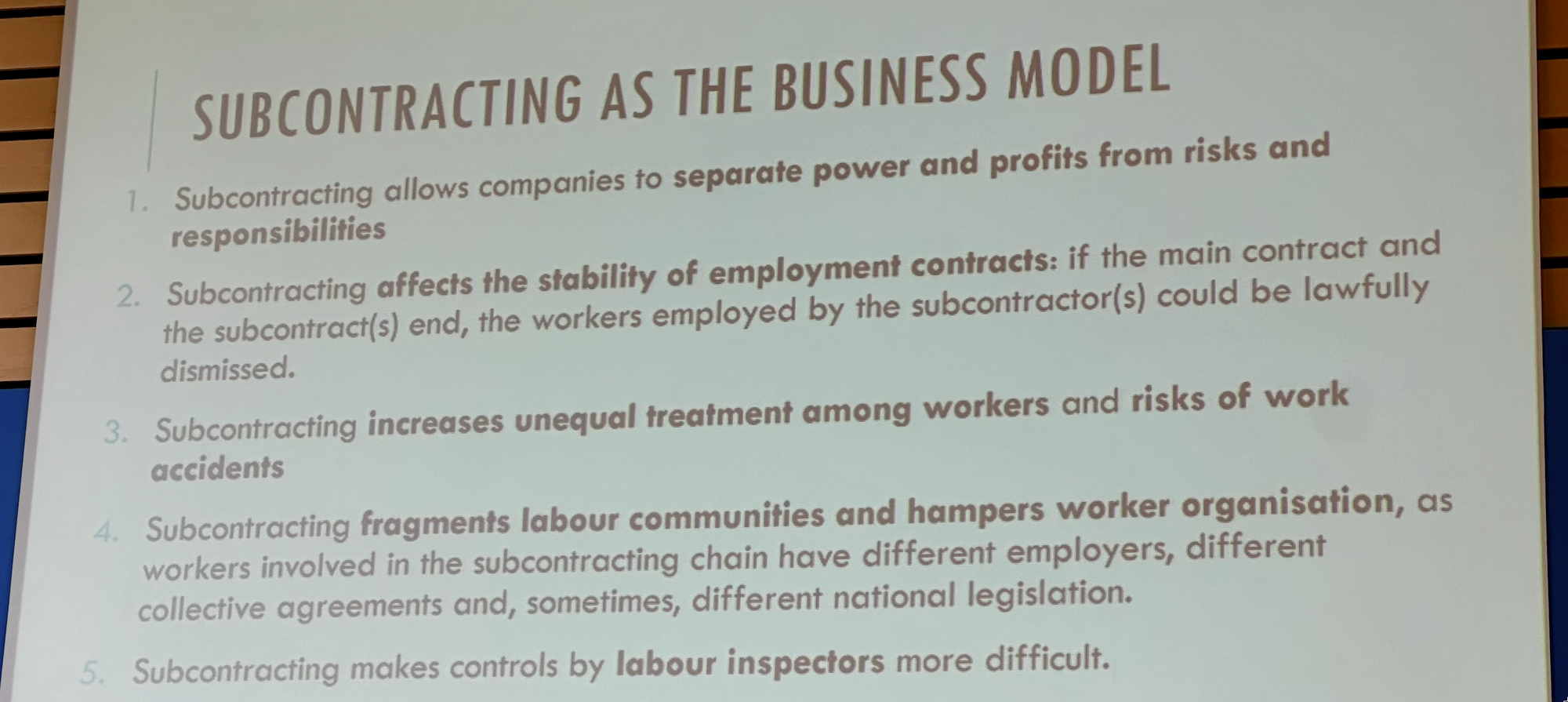

The employee paradox also lacks room for nuance. Employing means, for many platforms, switching themselves to the temp model (with limited rights) or using existing temp agencies or subcontractors. Randstad’s CEO a few years ago, for instance, named the ‘gig staffing market’ as one of the big opportunities for the staffing company. One of the conclusions from the aforementioned paper I wrote with Jeroen Meijerink is that many types of platform work can be perfectly well organised via a temping model, with the important note that the terms ‘security’ and ‘fairness’ under these models are not of the level as they are presented to us in the public debate. And that it becomes very difficult for employment agencies to comply with the legal duty of care. Something that also came up in the contribution by Silvia Borelli (Università di Ferrara).

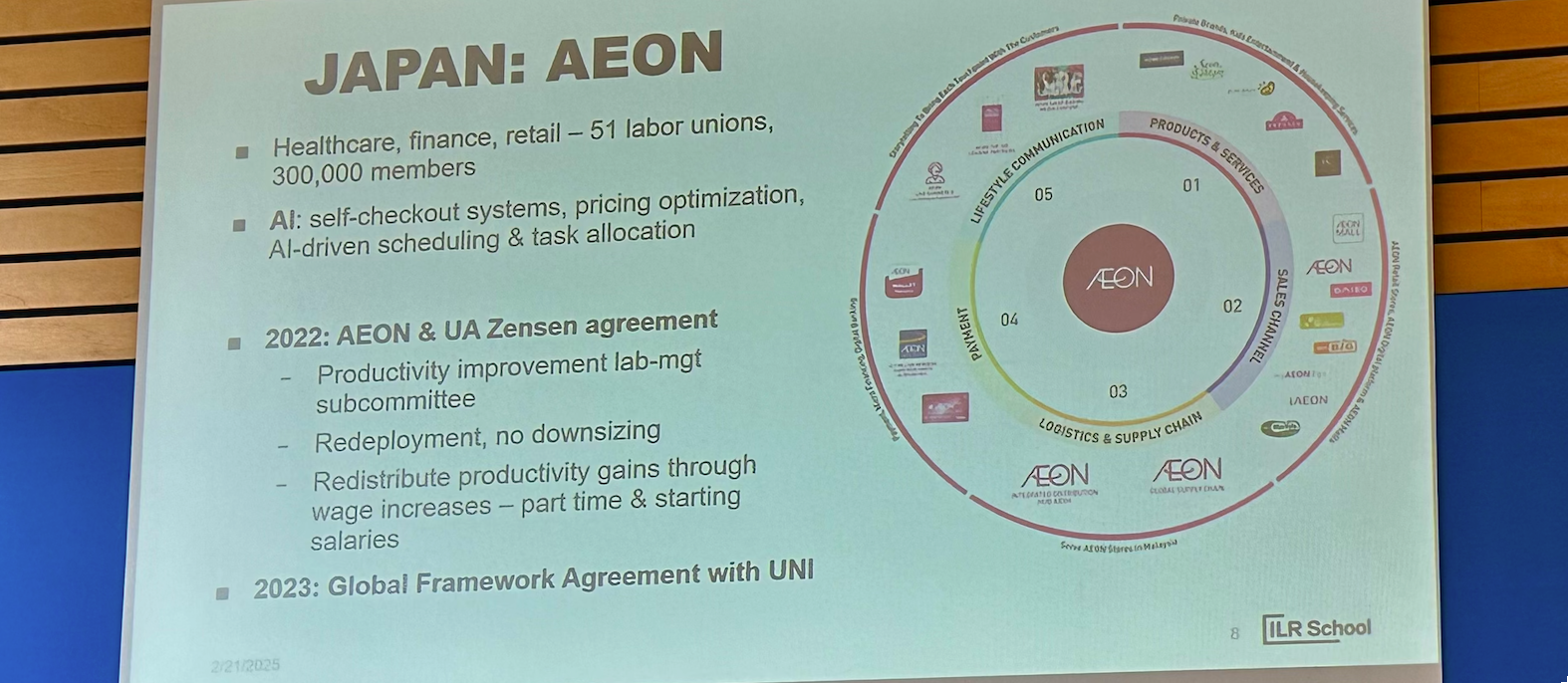

The conference presented several examples of how ‘worker representation’ in digital technology and AI can be organised.

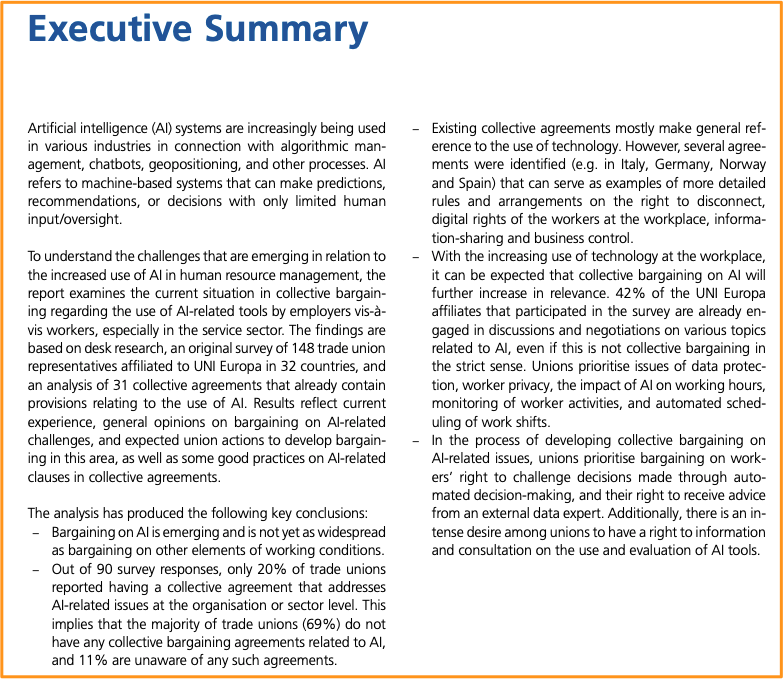

A subject that will only become more important in the coming years. Here, unions face a dilemma: do they stick to the existing model, or do they initiate a change to a more broad focus on ‘the workers’ in the broadest sense of the word and build up expertise to also stand up for workers in the digital domain. Visitors to the conference agreed that unions currently give far too little priority to this, something also acknowledged in the report ‘Collective bargaining practices on AI and algorithmic management in European services sectors.’

I challenge unions to then instantly look a bit wider and examine whether they may need to target not only employers, but also mediators and the creators of technology. In the digital domain, it is more necessary than ever to fight for a better balance of power, which will ultimately also lead to better products and innovations. Trade unions could and (in my opinion) should play an important role in this.

What is a decent income? Towards a more global view

A topic that doesn’t come up much at these kinds of conferences is the topic of income. Or rather, decent income. When it comes to income, the topic is usually the intransparency of payments in on-demand platforms like delivery and taxi. An important topic, as these platforms have only made the structures of how a tariff is built more complex over the years, so the worker often does not know what the earnings are before accepting a gig and the gap between what the worker receives and what the customer pays has grown. In a market where transparency was promised, information asymmetry has only grown to the disadvantage of workers.

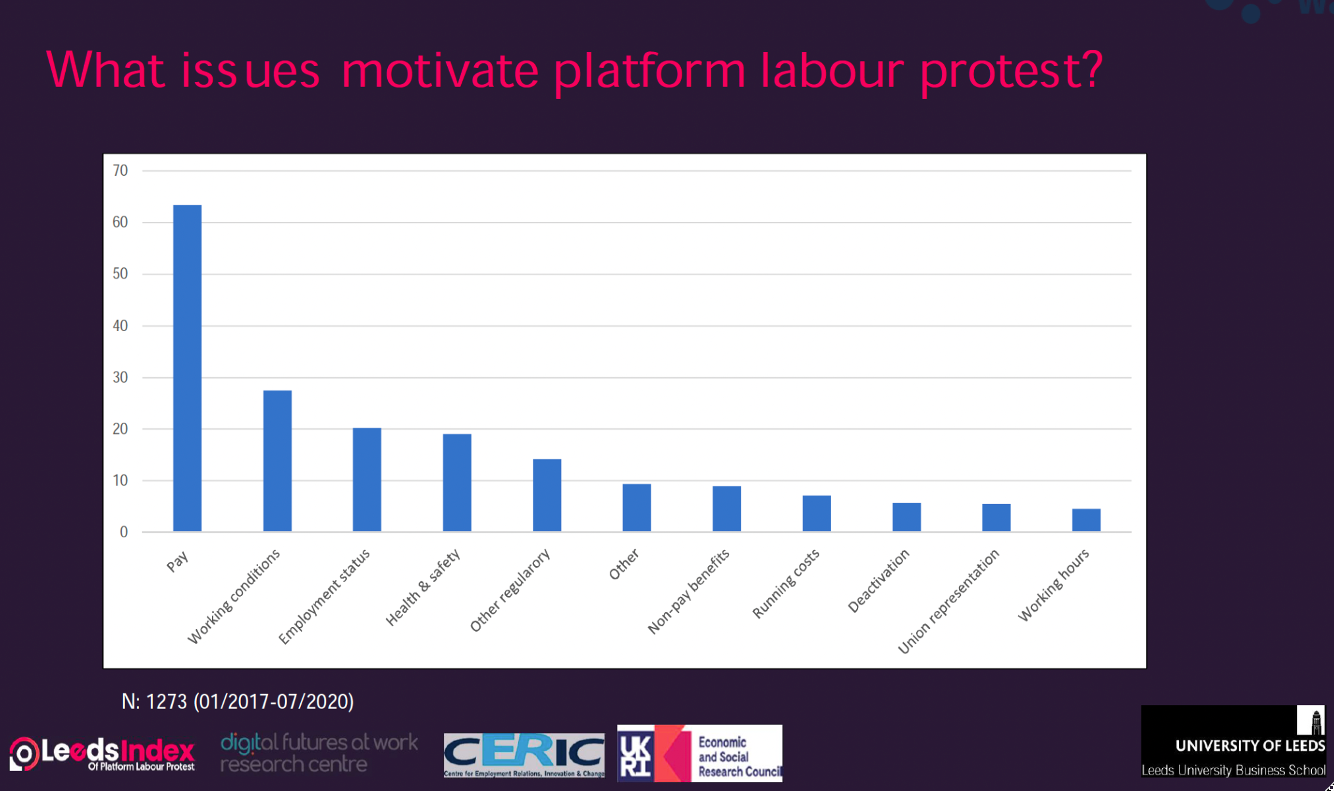

Besides the issue of transparency (it is questionable to what extent dynamic tariffs for work are at all desirable), there is no debate on the level of compensation a worker should receive for the service provided. A topic that is ranked number one when you look at what platform workers are taking to the streets worldwide for, according to earlier research by Leeds University.

💡

Check also the blog and podcast I produced “How and why does the platform worker protest? Scientists provide overview and insights”, based on an interview with researchers Vera Trappmann and Simon Joyce.

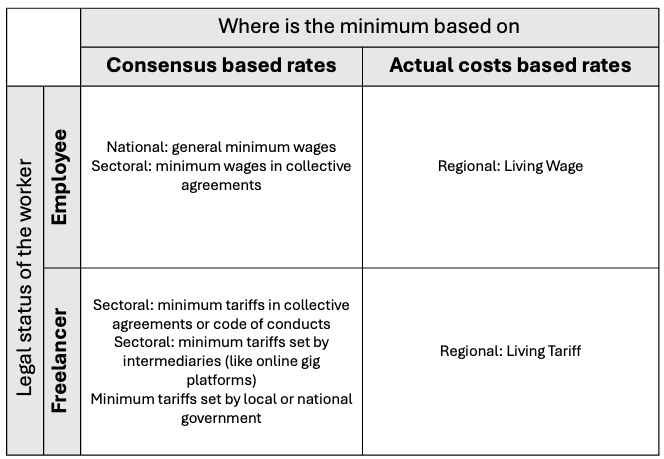

That was therefore the topic of my contribution: ‘Facilitating workers and policy makers in the gig economy making better informed decisions: the case study of the Living Tariff’. The basis of this concept comes from the Living Wage methodology, where a minimum wage for a worker is calculated based on the costs a worker has to incur to live a decent life in country X in region X. A wage floor based on actual costs. Where the Living Wage is of value to employees, someone who is not an employee can do little with it. Whereas certain costs and risks of work in the case of an employee are borne by the employer, a non-employee (freelancers and informal market) has to bear these costs and risks themselves. These should be included in the hourly rate to arrive at a fair minimum threshold.

💡

Last year I interviewed Valeria Pulignano, who is in the lead of the Respect Me project, for The Gig Work Podcast by the WageIndicator on her research on unpaid labour. Check the podcast and blog.

With the Living Tariff methodology, these costs and risks are taken into account, allowing the freelancer to know what they need to earn per hour to eventually arrive at a Living Wage, after deducting risks and costs. This methodology fills an important gap in the calculation of minimum income (wages and tariffs).

A next step is for this calculation to be included in consultations with various stakeholders (clients/platforms, workers/trade unions and policymakers/politics) in a discussion on fair compensation for workers. If you want to know more about this, check out the Living Tariff page, the slides I used for my presentation, or the blog and podcast I produced on this topic.

To conclude

It was a delight to attend this conference, hear the insights of researchers and then have great conversations and discussions about this. What I would like to see is a sequel to a conference like this, but with a broader stakeholder perspective. At the opening, someone in the audience asked ‘are we also going to talk about opportunities?’. A fair question, but in order to arrive at exploiting opportunities (and reducing risks), an insight from different stakeholders is needed. Insights from policymakers and platforms themselves, for example. Now platforms have an image problem due to the sometimes questionable practices of some big players, but the market of platform companies is in fact mainly an SME market. According to the ‘Monitor online platforms 2023’ (CBS, 2023), 64.2 per cent of the 1,600 Dutch platform companies have 2 or fewer employees. Only 5 per cent of these companies have more than 100 employees. Those opportunities may not come directly from the big players, but there are plenty of small(er) platform companies that are a lot more approachable where positive change could come from. Whereas now there is sometimes a bit too much emphasis on struggle, which is explainable because of the union and collective action perspective, it would also not be wrong to apply experiments on a smaller scale with parties that do want to collaborate. And to take the lessons from there and scale them up. This also includes a discussion on the more fundamental questions about the value of work. The title of the conference was ‘reclaiming the value of work in the digital economy’. This is a step that, as far as I am concerned, is often skipped, because it also involves a piece of self-reflection on parts of the (vulnerable) labour market that are not included in the debate.

I am convinced that there are still plenty of opportunities, only it is up to those involved to take responsibility and take up, test, validate and scale up these opportunities. I am happy to contribute to that.