Is a platform worker employed by the platform or not? While the Dutch court ruled that this is indeed the case for Helpling’s home cleaners and Deliveroo’s meal delivery drivers, it is not always the case for Uber taxi drivers. One driver may be self-employed, another an employee. What does this ruling say about the labour market? According to me, we are not asking the right questions, which is why the discussion keeps repeating itself.

The ruling: it varies from case to case

Last week, the Amsterdam Court of Appeal ruled on appeal that taxi drivers who work as self-employed persons via the Uber app are not necessarily considered employees. Whether they are legally self-employed or employees varies from case to case. If a driver truly behaves as an independent contractor, he may be allowed to work as a self-employed professional. This is the case, for example, if he invests in his own car, bears his own business risks and chooses when and at what rate he works. If he is not sufficiently independent in this respect, he is an employee.

The case has been going on for quite some time. In 2021, the court ruled in favour of the FNV and, on appeal, the court of appeal referred preliminary questions to the Supreme Court. Last week’s ruling: the six drivers who joined Uber’s appeal are not employees, but self-employed workers. The judge emphasised that drivers who use the platform can be employees, but that this must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

The union’s intention

This lawsuit is part of a series of cases brought by Dutch union FNV against platforms. According to FNV, workers in the platform economy should have the rights of employees or temporary workers. But who are they actually fighting for?

The FNV previously took legal action against the domestic cleaning platform Helpling and the food delivery platform Deliveroo. In the case of Helpling, it was clearly not about the domestic cleaners. In the case of Deliveroo, I am convinced that it was more about setting a precedent for the entire labour market than defending a handful of platform workers. That is a respectable choice, but in the context of the discussion, this goal must remain clear.

Where does this obsession with employee status come from?

In the Netherlands, employment is the norm, as it is in many other Western countries. Employees have access to benefits such as social insurance, unemployment benefits, sick leave and pensions. They enjoy protection around health and safety at work. They are covered by collective labour agreements and pension funds. To assert their rights, employees are allowed to organise collectively and be represented. This contrasts with entrepreneurs, who are subject to competition law.

In short, all securities and institutions are organised around employment. Self-employed entrepreneurs in the Netherlands must figure it out for themselves. This dichotomy also leads to differences in price, which creates competition on employment conditions, especially at low rates. So it’s all or nothing, which is why the classification question (employee or self-employed?) is so important. But this issue also turns out to be very complicated.

What are platforms really changing?

The rise of the platform economy has intensified the debate. I always ask myself: what is the impact of a platform entering the market? How was the sector organised before? After all, domestic cleaners, food delivery riders and taxi drivers are not new types of jobs. What is the platform company’s strategy and what changes will it bring?

Helpling: virtually nothing

In the case of Helpling, very little changed. Twenty-five years before Helpling entered the market, there were already websites for arranging domestic cleaning services. Helpling simply made it easier to establish initial contact. A second appointment can easily be arranged without using the platform.

So there was no risk of an undesirable dominant position. Helpling’s competitors were not cleaning companies, but the informal market. When the court ruled that the cleaners were temporary workers, the platform went bankrupt and the cleaners “returned” to the informal circuit. Attention to the precarious position of this group of workers thus disappeared, despite alarming reports about the failure of the Home Services Scheme. This is a scheme in the Netherlands that relieves private employers who hire help in and around the home of certain employer responsibilities.

Deliveroo: uncertainty and fear

The arrival of Deliveroo and its competitor Uber Eats did indeed lead to change. Previously, the market functioned very poorly: meal delivery workers were usually employed by the restaurants themselves.

But Deliveroo did not make things much better. Firstly, the two platform companies ensured that delivery drivers worked as freelancers rather than employees. They were paid per order rather than per hour. That model was opaque and it got worse and worse. In addition, the unclear algorithms often had a negative impact on couriers, which led to fear, especially among those who depended on the platform for their income.

The Dutch company Thuisbezorgd (Just Eat Takeaway) proved that platforms do not have to have a negative impact. This company did employ meal couriers and even received an award for applying digital applications for health at work.

Uber: a battle for the trade union

Taxi app Uber entered the street taxi market. Self-employment was already the norm for drivers, and taxi companies had their own ways of matching supply and demand for taxis. Although using technology in the operation of the taxi market was not new, Uber’s approach brought about enormous change. An aggressive (or ambitious?) strategy, an unprecedented international scale, and smart marketing and lobbying.

Uber lowered the threshold for becoming a taxi driver and for ordering taxis. The model was “on demand”, which had a major impact on access, allocation, management and assessment of work. It became unclear how the driver’s fee was determined. Read this analysis about a study into income.

There was no human point of contact, let alone a structured framework of rules, roles, responsibilities and decision-making procedures. In short, there was definitely something for the trade union to fight for.

The wishes of platform workers? Often irrelevant

But what do workers want? This is not relevant in labour law, and unions also pay little attention to it. After all, trade unions represent a collective interest, or so the thinking goes. Yet it would give trade unions more context if they listened to individuals more often. Moreover, it would strengthen their legitimacy as representatives, something that was a point of discussion in the ongoing case against Temper, the FNV’s fourth major Dutch platform case.

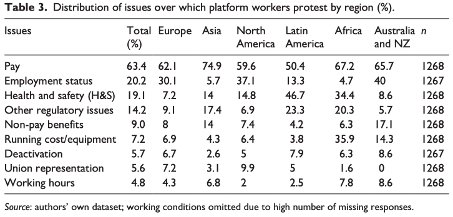

The Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest offers an interesting insight into what workers want. I spoke to the researchers a while ago in my podcast. In this paper (based on more than a thousand protests), they also share the motivations of platform workers to protest. It turns out that this varies greatly by region, profession and economic situation, but by far the most complaints worldwide are about remuneration.

What strikes me in the ruling

Back to the court ruling in the Uber case. This shows once again that classification is complicated. It remains a matter of customisation. Whether someone is allowed to work as a self-employed person is apparently difficult to determine per group or sector. This discussion is therefore likely to continue for some time.

1. Little attention to technology and algorithmic management

I have not read the entire judgment and have no legal background, but as a platform expert, a number of things stand out in the judge’s explanation. For example, I am surprised that so little attention is paid to the role of technology in the distribution, execution and assessment of the work. This is striking, because the arrival of Uber has had a huge impact on algorithmic management in the taxi industry.

2. Major investment: independence or dependence?

Another interesting detail is that whether a taxi driver invests in a car himself is taken into account in the assessment. This is even though such a substantial expenditure can lead to great dependence.

3. Focus on labels, not on well-being

I also find it disappointing that there is still such a strong focus on labels (are you an employee or a self-employed person?) and so little on working conditions in practice. This may be logical from the perspective of our Dutch system, but in practice, after six years of legal battles, nothing has changed for taxi drivers. In other countries, I see that unions are sometimes more flexible and focus on agreements about the content and conditions of work. This means they do not first have to fight for legal status in court.

Is employee status the only solution?

This brings me to the point: are we asking the right questions? Yes, employee status would automatically solve several problems in the sector. At present, platforms such as Uber and Bolt thrive when there is an oversupply of drivers. Customers always get quick service. But the associated unpaid labour is entirely at the expense of the self-employed driver. If he were employed, those costs would be borne by his employer. Employment also puts an end to discussions about non-transparent calculations of remuneration and the right to insurance and pensions.

However, this ruling shows that claiming collective employment status is very difficult. In addition, an employment contract often means a temporary employment or payroll construction. Do these flexible contracts really offer all the benefits? In other countries, questions are being raised as to whether temporary employment agencies will be unable to fulfil their duty of care if platform apps take over the entire planning and management.

Finally, it is important to realise that platform work is not suddenly well rewarded when employees become salaried employees. The consumer is perhaps the worst possible employer.

The right questions

We would do better to ask ourselves how we can prevent competition between the different types of contracts. Not contract-specific insurance, pensions and rules, but contract-neutral provisions.

A practical example is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This European law applies to individuals, and research shows that workers have ample opportunities to assert their rights under this law. The upcoming Platform Work Directive also contains contract-neutral solutions for the protection of workers.

Experiment with all stakeholders

The platform economy is seen as the breeding ground for labour market technology and the future of work. So let’s use platforms to experiment with fair representation, co-determination and responsibilities in the digital world.

This is already happening. Read, for example, my story about the Worker Info Exchange in the United Kingdom. Or my piece about the Colombian platform Hogaru, which, unlike the government, is able to reach invisible cleaners and inform them about their rights and, as a kind of payroll provider, facilitates private households in hiring domestic help.

There are also initiatives in the Netherlands. For example, I started GigCV, where platform workers can take their work performance data with them in the form of a digital CV. I am also involved in the Living Tariff, a minimum rate for self-employed workers based on a Living Wage. The fact that you can enforce such a minimum rate was proven in the state of New York. Since 2023, 60,000 workers (according to their own figures) have together received more than 700 million dollars of extra income.

So there are already examples, but as far as I am concerned, there should be many more and they should be given greater priority. They help us to rethink existing, outdated working methods, rules and choices. It is not the status quo or the market, but sound insights and considerations that should form the basis for deciding what we as a society do and do not want. Such as complex, dynamic pricing mechanisms for work.

To conclude

The debate is now at a standstill. The focus is entirely on the legal status of workers, which distracts from the real goal: a well-functioning labour market with fair rights for workers. I therefore advocate a diverse, open approach. Let’s create space to work together on a better labour market for all workers, even if we disagree on whether they are self-employed, employees or temporary workers. Let’s agree to disagree.